Tennis has always been a rich kids’ sport, and so the 1978 team at Ann Arbor Huron High was full of the sons of doctors, law professors, and Ford engineers. Our best players were Jewish - especially my friend Jon who later won the Big 10 – but most of the players had names like Cox, Shepherd, and Carrington. We had an African-American kid on the team the year before, but he had graduated and left my friend Tom Kumasaka as the only non-white on the team.

Tom had befriended me in 1976 when we both had started at Huron. We bonded over tennis in the back row of advanced classes in French, Chemistry, and Physics, in which he excelled and I scraped by. I had few friends in junior high and then, because of districting lines, they all went to the other public high school in Ann Arbor. The Huron tennis team therefore became my group, especially through Tom and my late friend John Turcotte, and I was lucky to have them as friends.

Tom and George Shepherd formed a tremendous doubles team in 1978 and, indeed, though our team won the state title that year, Tom and George were the only ones who won their individual flight. Tom and George’s quickness created an impenetrable net presence that overwhelmed every other team in the state. I’ve still got my state championship medal thanks to Tom (and George). Tom was a graceful singles player, too, with a beautiful slice backhand that I still copy.

I haven’t talked with Tom in 45 years, at least in part because my family moved to North Carolina immediately after we won that title, but Oppenheimer has me thinking again about the war with Japan – including Pearl Harbor and the atomic bomb, but also about the internment of Japanese-Americans in concentration camps for much of the war. That has in turn got me thinking once again about the experience of Tom’s family during the war.

The fact is, however, that back in high school I didn’t know a damn thing about Tom’s family’s experience. I was obsessed with WWII as a kid - reading hundreds of books, playing war-themed board games like Midway and Leyte Gulf, and watching every movie I could - and so I was well-aware of the wartime internment of Japanese Americans. But that was simply something that I never talked about with Tom and that he never brought up with me. I spent several nights at his family’s beautiful modern house near the Huron River, where I met his parents and where Tom teased his little brother, but we gossiped about tennis rather than speaking of history.

The reluctance to talk about internment did not reflect an overarching sensitivity by myself or my friends to issues of race, ethnicity, or even what might today be called generational trauma. Tom and I made lavish fun of our French teacher Mr. Karamanoukian, an artist and Sorbonne graduate born in 1940 in Paris to Armenian refugees. We also made regular fun of our classmate Peter Darvas, and how his family had left Hungary in 1956. And I felt particular license to make fun of the English kid whose family had moved to Ann Arbor from Malta. Kids are terrible, and Tom and I were kids. I’m not sure why WWII in America never came up.

The US interned about 120,000 Japanese Americans during the war, about two thirds of them US citizens born in America. The vast majority of these internees resided in California, Oregon, or Washington, and if the adults had children, then the children went to the camps, too. By contrast, most of the Japanese-Americans of Hawaii were not interned, not least because, as roughly 30 percent of the islands’ population, internment there was impracticable.

Japanese-American internees who returned after the war often found that their homes and their property had been appropriated by their neighbors. Some got their property back, some didn’t, a story at the center of David Guterson’s Snow Falling on Cedars. The story is a common theme of WWII, most notably in Poland, where gentiles quickly occupied nearby houses and farms after the Germans had taken away their Jewish occupants. Even the Jews who survived never got their property back.

How did Mr. Kumasaka’s story fit into this broad narrative? I hadn’t asked as a kid, but Mr. Kumasaka’s obituary in the Ann Arbor News in 2014, surely written by Tom and his siblings, says the following:

Glen was born in Tacoma, Washington on January 15, 1929. After spending the war in the Tule Lake internment camp, his family relocated to Rochester, New York where he attended Eastman High School. He received a BA from Harvard University and his MD from the University of Rochester in Rochester, New York. He met and married Ruri Yamashina in Los Angeles, California. After a short courtship, they enjoyed a marriage which lasted over 53 years.

Glen had retired from a 28-year career as a radiologist at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in Ann Arbor. During his retirement he enjoyed watching his grandchildren flourish and worked for years on his soon-to-be published memoirs. Glen loved his family, friends, and classical music. He would usually complete the New York Times Sunday crossword puzzle without difficulty. Glen will be remembered as a kind and humble man who never felt comfortable being called “doctor.” Like his father, Glen was ever-grateful and wrote in the anniversary book for his 50th college reunion that he hoped to be remembered as someone whose whole life was `blessed by the most fantastic luck.’

Glen was obviously, during World War II, subjected to some very bad luck, but his kindly, optimistic mood was obvious whenever I ran into him with Tom.

It appears that Glen Kumasaka’s memoirs remain unpublished, but other memoirs speak of life in the camps. Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston’s Farewell to Manazanar (1973), for example, recounts how her father learned of Pearl Harbor while on his sardine boat and how, though he burned his Japanese flag back in Long Beach, the family was soon relocated to Manzanar in the high California desert. The camp at first had inadequate shelter and clothing, and Mr. Wakatsuki became an alcoholic during and beyond his time in the camp. Jeanne’s older brother grew to lead the family and served in an Japanese-American unit in Europe. Jeanne resented but ultimately came to understand her father’s behavior and, as an adult, she had three children with her Anglo husband.

Yoshiko Uchida’s Desert Exile (1982) describes her childhood in Berkeley, California as the daughter of Japanese immigrants. Uchida’s childhood was happy but, like many other children of immigrants, she felt alienated and rejected both by white Americans and by traditional Japanese culture. As Ucheda says, it was “small wonder that many of us felt insecure and ambivalent and retreated into our own special subculture where we were fully accepted.” Ucheda enrolled at the University of California in 1940 and, feeling unwelcome elsewhere, happily affiliated with a thriving subculture of Japanese American clubs.

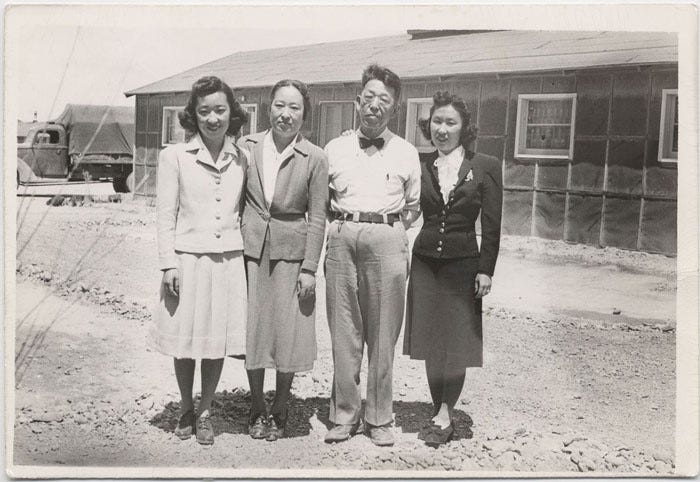

Then Pearl Harbor happened. Uchida’s father was detained, she heard of rural violence against Japanese American farmers, and she was herself accosted in a Berkeley restaurant by a Filipino American angry with the Japanese Army’s invasion of the Philippines. Her family was soon moved to an Oakland racetrack and then to Topaz, a dusty internment camp in Utah. Ucheda and her sister were released in 1943 to attend Smith College, but her parents remained at Topaz for the rest of the war. You can see the Ucheda sisters below, with their parents on the day they left the Topaz camp.

WWII brought Americans together in many ways, some of them heroic, and together the nation did vanquish the vile regimes in power in Germany, Italy, and Japan. We are and should be proud of those facts. Yet the war pulled Americans apart in ways that were predictable given our experience in prior conflicts, and the internment of Japanese Americans was only the most extreme example of those unravelings.

Lou Gehrig was born and raised in Manhattan, but his first language was German and, during WWI, he and other German kids were the subject of bullying and abuse. It wasn’t just the kids, either, as German words were purged from the names of streets and institutions and several thousand German immigrants were interned at Fort Douglas in Utah. Internship was part of the Wilson administration’s wide-ranging suspension of civil liberties during the war. The U.S. would have interned more German-Americans during WWI if their vast numbers had not made doing so impracticable.

The American involvement in WWII was longer and more intense and, partly as a result, the suspension of civil liberties was longer and more intense, too. As Oppenheimer shows, the war brought renewed anxiety about German, Japanese and especially Russian spies. This in turn brought surveillance of suspected spies to a new level, and while there really were some spies, such as Oppenheimer’s Klaus Fuchs and Japanese agent Takeo Yoshikawa, the net effect was that many innocents were oppressed.

Ethnic strife and suppression were also heightened during WWII. German-Americans were bullied again but, as in WWI, their large numbers precluded any serious effort to intern them. Indeed, several of Hitler’s nephews lived on Long Island during the war, and Kitty Oppenheimer herself was born in Germany and was a cousin to a Nazi Field Marshal. Italian-Americans were also harassed and, in a few cases, even interned, though these patterns were largely reversed after Italy switched sides at the end of 1943.

There was even heightened strife against ethnic groups not connected to the Axis powers. The Roosevelt Administration brought in tens of thousands of Mexicans to work in jobs vacated in 1942 by Americans inducted into the services. The Mexicans’ work was essential to the war-time economy, but they were also resented by American servicemen moving through western ports on their way to fight the Japanese. To these soldiers, in anonymized uniforms and on their way to death and disease in the Pacific, it was enraging to see their replacements wearing the flashy pants and jackets popular among Mexican youth of the day. The result was the Zoot Suit Riots of 1943.

Some will read these events as yet another sign of Americans’ intrinsic racism and bigotry, and of course they’re not entirely wrong. Yet there is a human tendency, not particularly American, for dominant ethnic groups to look balefully at minorities in times of threat and stress. In different ways, these fears were the source of genocides as disparate as the Holocaust, the Hutu’s mass killings of Tutsis in Rwanda in 1994, and the Armenian genocide of WWI that drove Mr. Karamanoukian’s parents to France. There are endless other examples. It would be nice if the Americans were free of these failings, but of course we aren’t.

The U.S. was also not alone in interning native-born citizens during WWII. Canada and Australia, for example, both interned their ethnically Japanese citizens during the war. Britain interned thousands of German immigrants during the war, even though most of them were Jews or other refugees of Nazi oppression. Japan itself interned thousands of British and Americans during WWII, and likely would have interned more if there hadn’t been so few foreigners living in Japan in 1941. J.G. Ballard’s Empire of the Sun (1984) presents one British boy’s horrific experience of internment in a Japanese camp in Shanghai.

Some of the children of the Japanese American internment camps went on to great things as adults. These of course include Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston and Yoshiko Ucheda, but also men like actor Pat Morita (The Karate Kid) and Bob Hamada, Dean of the University of Chicago Business School. Internee Daniel Inouye lost his right arm serving in Italy and was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1962. He served for nearly 50 years, gaining fame and respect on the committees that investigated the Watergate and Iran/Contra affairs.

Mr. Kumasaka went on to great things, too, having a long marriage, a career as a radiologist, and raising wonderful children. You might think it odd, given his wartime experience, for Mr. Kumasaka to have attributed his success to luck, but there was at least one sense in which he was extraordinarily lucky. The quote and picture below are from a modern website devoted to the history of Tacoma, Washington:

“Why were these two kids getting their picture taken by a professional photographer in October 1934. The reason is actually pretty cool. This is Ruby Kumasaka who is seven years old and her brother Hisasha (later to be “Glen”) who is five. They lived in an apartment in…in the heart of Japantown. An unusual thing about their family was that for all of their young lives their household had included a “grandfather” named Sweny Smith who was born in mid-1800’s Norway, some 80 years before this picture was taken. Sweny was an old deep woods logger and practicing Buddhist who became friends with the kids’ young parents.

When age and years of hard work made it difficult for him to get along by himself, the Kumasakas invited (Smith) into their home to live. He lived with the young couple during the birth of both their children, celebrated Japanese and Buddhist holidays with them and settled easily into their daily customs of food and language. In his 80th year Sweny Smith passed away in bed after living almost a decade with the Kumasakas in a modest apartment in Tacoma. Before he died he told the children, like a grandfather Buddha, that like a pearl of great price, life would be good for them. He then directed them to a deposit box in a big downtown bank where his will left each of them $10,000, small fortunes during the depth of the Depression.”

Difficulties like the Depression or WWII often bring out the worst in people, especially across groups defined by race or ethnicity, but we should not forget that there are still bonds such as that between the Kumasakas and Sweny Smith. The picture below makes me smile.

A beautiful piece of writing. Did you ever get back in touch with Tom?

Wonderfulcilumn, complex and thoughtful. Thank you Wiil.